Questions and questioning is a substantial topic and unsurprisingly contributes significantly to an area of professional interest – testing enhanced learning. What follows is a short post prompted by a visit to a Christmas pantomime and the past three years focus on testing as learning.

What to question?

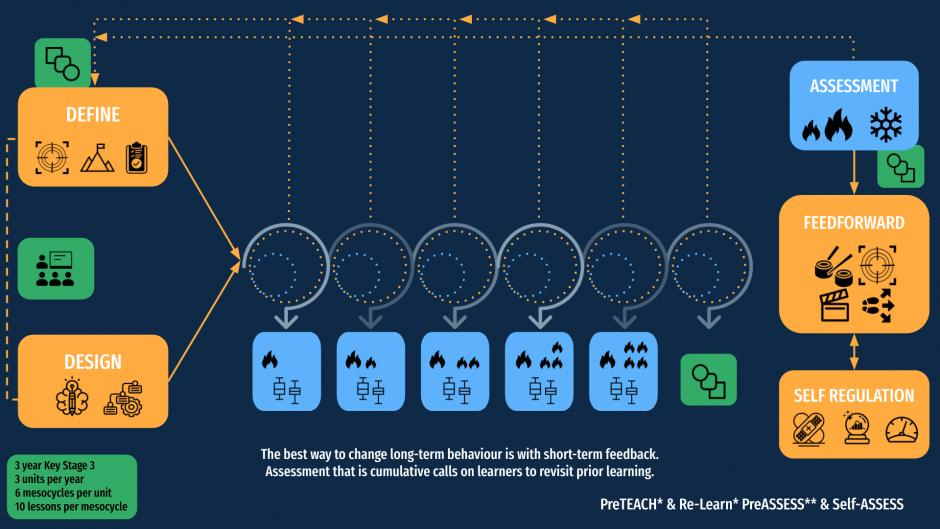

After very carefully selecting what I want pupils to ‘know and remember,’ next I very carefully consider how I will know, that pupils confidently know and are able to remember, what it is I have very carefully selected and teach them. That thinking starts with the composition of final assessments, meso-assessments as shown below in a typical termly model. More often than not, I will also plan key learning activities and questions.

Learning design, that includes questioning, is a highly complex and messy process and asking questions, of various types and for various purposes, plays an important role in both learning/encoding and maintenance/relearning processes. I minded to signpost Ted Wragg’s 2003 Teacher’s TV video to underline just how important.

Teachers ask up to two questions every minute, up to 400 in a day, around 70,000 a year, or two to three million in the course of a career. Questioning accounts for up to a third of all teaching time, second only to the time devoted to explanation.

Ted Wragg (2003)

What a cheese sandwich can teach us about questioning at this point. At this point; next to nothing. Stay with me.

Setting aside potentiated questioning and terminal assessments or tests, I am looking at questioning to ‘check for understanding’ during encoding/learning and to promote maintenance / relearning (although what I am about to discuss applies to all questioning opportunities).

Designing questions is a complex and artful proposition. We know Let’s propose we want pupils to know X.

- What it is you want pupils to know impacts the question (eg complex knowledge, a procedure or sequence, to a simple fact, a name or date)

- How well your pupils need to know X impacts the question (eg explicitly/flexibility to being able to offer a general idea)

- When pupils learnt or last relearnt X and when that knowledge is needed, impacts the question (eg retrieval and storage strength, assessment date)

What I have been mulling over for a month or so is this.

Questioning, particularly the common classroom interrogative variety, may be more effectively thought of as a diagnostic cue than a question. That is, a diagnostic cue should explicitly target and diagnose the answer. Second, that the weaker the retrieval and/or storage strength or the more complex the knowledge or X – the more explicit the diagnostic cue must be. For example.

Colour – six letters?

This question has poor ‘diagnosticity’ with many possible answers: Maroon, Orange, Purple, Silver, Violet…

Colour – six letters? _ _ L _ _ _? Improved diagnosticity.

Colour – six letters? _ _ _ _ _ W

ANSWER: Yellow, with this colour having low complexity, high retrieval and storage strength.

What a cheese sandwich can teach us about questioning. So, now for the cheese sandwich

In a lesson, you need pupils to be able to service X when prompted by cue Y. In education, with Ted Wragg’s comments in mind, that cue Y is most often a question.

Servicing X follows understanding cue Y. Then being able to retrieve and reconstruct one’s knowledge to coordinate and service an answer. The correct answer can not be accessed if cue Y does not diagnose the required target information X.

Knowledge cannot be examined without a retrieval context. Let’s use a recent visit to panto to illustrate my point. At the close of the panto, two young children are on stage vying for ‘goodie bag.’ Richard Cadell asks the eight year old audience member on stage the follow question or diagnostic cue:

“What do you put in a ‘cheese’ [emphasis] sandwich?”

The audience, including myself, offer a low chortle. The audience is willing the young boy on. We clearly heard and understood the emphasis on ‘cheese.’ We clearly understand the context. The boy senses ‘something’ and readies himself with a deep breath before answering.

“Pickle.”

The young boy’s response is met with laughter and warm applause. Richard Cadell rests his head against him arm and sighs.

Of course “pickle” is the answer. What else would you put in a sandwich – that already has cheese in it! Second, think about it from an eight year old’s perspective: the answer would not be cheese because questions do not usually include the answer – as a part of the question.

What a cheese sandwich can teach us about questioning?

Is there such a word as diagnosticity? Yes, but it is in relation to data. So I am borrowing it to help describe effective question design.

During learning/encoding

Where knowledge is complex or retrieval or storage strength is low – diagnosticity should be high.

- Match (recognition)

- Multiple choice (recognition)

- Cloze questions (context)

- Employ very high success rates

- Fewer questions, repeated cycles

- Narrow focus

- Where knowledge is complex, employ multiple questions or cues

- Use hints (eg cued first letters)

- Record corrected answers

Maintenance and relearning

Knowledge is more secure, retrieval or storage strength is high – diagnosticity should remain high, however greater cognitive retrieval demands should be made

Free recall

- Retrieval is fast

- Employ very high success rates

- Broaden focus and ask more questions (in the same time)

- Interleave the topic

- Where knowledge is complex – seek multiple parts

- Elaborate

The accessibility X and diagnosticity of the question cue are two essential elements of questioning. Even when knowledge is accessible, the diagnosticity of the question can lead to variable learner performance.

It is clear that in a classroom that values testing as learning, learners benefit from being asked questions with high diagnosticity and being required to ‘retrieve and reconstruct’ their knowledge.

And lastly, not all learning gains are immediate. That is certainly the case when investing in and building pupils’ vocabulary. There’s strong evidence to connecting a child’s vocabulary at 24 months with performance on measures of maths, reading, and behaviour at age 5. With vocabulary at age five a strong predictor of the qualifications achieved at school leaving age and beyond, (Spencer, et al., 2017). Explicitly clear evidence for the profession to take heed of.

As for ever increasing time demands and time pressures that I am confident teachers will rightly challenge me with. It is worth remembering that Rawson et al. (2018) reported that correctly recalling items one time across three sessions versus three times in one session yielded a whopping 262% increase in retention test performance. Invest, teach and reteach – with the long term, durable learning gains in mind and the richer conversations and classroom discussions that will undoubtedly follow.

Takeaway

When designing questions – ensure high diagnosticity. Does the question explicitly target the answer?