Whenever I need help with a tricky ‘Science of Reading’ query, Chris Such rarely fails to respond with multiple possible responses. And rightly so, the Science of Reading is a complex and interwoven topic. His book, sadly, is mistitled – “The Art and Science of Teaching Primary Reading.” It is essential reading for all teachers and his Twitter thread @Suchmo83 is a rich vein of commentary worth mining.

Now, in light of reviewing Sarah Cottingham’s new book ‘Meaningful Learning in Action,’ I am already looking forward to an extended conversation around how to tackle extended texts, plays and books. Even more so having given way too much time to “exploring that vast forest” that is Shakespeare ahead of teaching Much Ado About Nothing next term. Specifically, Much Ado About Nothing in Year 7 (or most of it), that then leads to Romeo and Juliet in Year 8 and Macbeth Year 10.

Why is reading a text likened to the “task of exploring a vast forest.” I will let Chris explain:

Imagine you’ve been given the task of exploring a vast forest with a group of kids who have never been anywhere like this before. The coach has dropped you off, and now you have a few short hours to help the kids appreciate the majesty of such a place.

How much time would you spend hiking along the forest path together, your eyes wandering and relishing the succession of fleeting, connected moments?

And how much time would you spend standing in one spot, touching the scaly bark of an alder, watching the dappled light dance on the forest floor, exposing a scramble of insects beneath a fallen branch?

There is a balance to be struck during such exploration between pausing to appreciate the surroundings and relishing the vigorous rhythm of movement.

As a guide, it’s worth trusting your instincts. They won’t develop otherwise. But if in doubt, get moving again. There will always be another spot to admire, and the forest has more treasures than can be seen in a lifetime.

Alternatively, you could just show the kids a tiny section of forest, and then quickly get them back on the coach and back to class so there’s more time to silently answer questions about what little they saw.But my goodness what a wasted opportunity that would be.

Chris Such

Ahead of teaching Much Ado About Nothing I want pupils to spend as much time as possible in the forest. I am keen for the pupils to have a ‘big picture’ view of the play, it’s themes, cast relations and possibly a smattering of context, something to hang their knowledge upon, before setting out on our first hike. Something they can refer to back if necessary.

Much Ado About Nothing has such wonderful scenes-ery to pause upon, to stand in one spot and enjoy (not the naked bottoms in the film opening scenes however). These moments deepen our understanding of themes and cast relations too. I will add, they are all the more spectacular second time around, with a fuller understanding of the play and the plays themes. I do like to revisit our favourite spots on the way out too, if we can.

I am not in favour of showing sections. There is something wholesome in the whole. I simply tell the pupils early and boldly that our task is ambitious and we expect their full attention and their commitment beyond it.

When planning to teach a new text, I see a vast forest, I want to explore as much as possible, however I also see a game of jenga.

This is exactly what I saw all those years ago with my South Bronx fifth graders. Even a simple reading passage was like a game of Jenga, with every block in the tower a bit of background knowledge or vocabulary. Pull out a few and the tower stands. Pull out one too many and it collapses. Sense and meaning are lost. My students were no less intelligent, eager, or capable than more affluent kids a few subway stops away.

Robert Pondiscio

I also listened to Robert Pondiscio on the Melissa and Lori Love Literacy (Ep. 146: Reading Comprehension is Not a Skill with Robert Pondiscio).

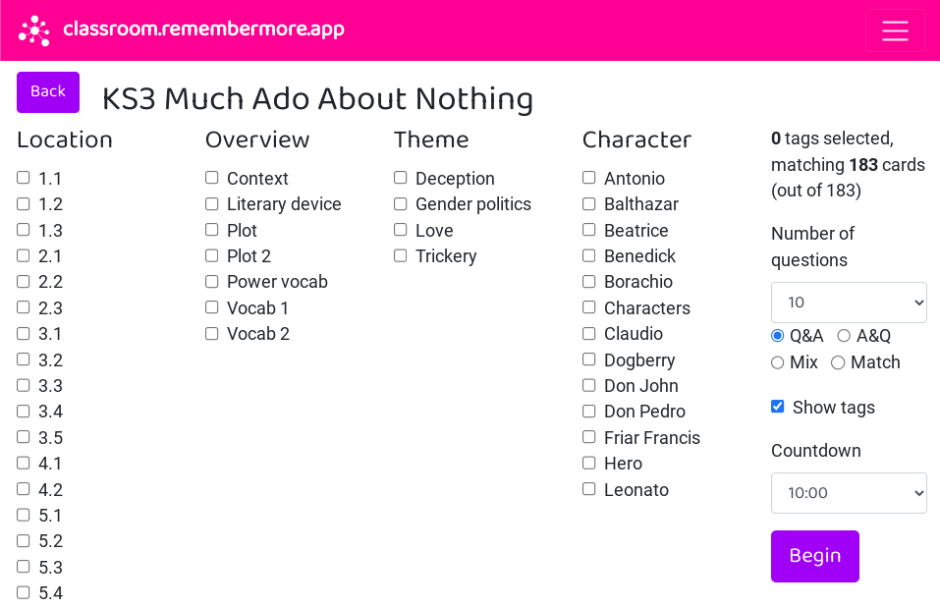

I am very particular about which Jenga blocks I teach, and which not. What plot is essential for these learners, what is not. What vocabulary and phrases from the text to pre-teach, what not, and what vocabulary is not in the text yet required to both understand and explore text eg patriarchy and illegitimate. I have even mulled over the relative value of understanding deception as separate to trickery, concluding that although both are methods of misleading or manipulating someone, they differ in their approach and intent and so both are taught. This information is woven together with classroom.remembermore.app available both in and out of the classroom, with test-enhance learning leveraged to maximise long-term learning and maximise time to explore in the forest. Of course, much of that knowledge is then called upon for the final assessment.