The support for #retrievalpractice (quizzing) is inexorable. Here, Shana Carpenter, Steven Pan and Andrew Butler take a more practical view of retrieval together with the second “high-utility” strategy spacing. Dr Carpenter was kind enough to share a readable view of the paper here.

Interestingly, Carpenter et al., (2022) open with the case that educational opportunities are becoming “increasingly autonomous, involving greater flexibility and more student-led decisions.” Hence, students now have “greater responsibility” for keeping themselves “on track,” to “monitor their progress and remediate their learning when necessary.” There is definitely a growing movement towards the importance of self-regulated learning. For most pupils in schools – that is homework and revision.

Spacing and retrieval are singled out as “straight forward techniques” “underused by learners” in part because of “false beliefs about learning and the counter-intuitive nature of the techniques.” That is after 100 years of retrieval research, 15 effortful years most recently, and education “could do better.”

Carpenter et al., (2022) position that successful learning requires:

…building factual knowledge as well as an understanding of how that knowledge can be integrated, utilized and applied in new situations. Memory for basic facts and concepts is needed to build a deeper understanding of how those facts and concepts fit into a broader network of knowledge, in turn allowing advanced reasoning and application.

Second, that “a more comprehensive perspective that permits deeper understanding can be slower to develop.” That these two “levels of knowledge,” “factual/conceptual” and “applied” are aligned with “retention” and “transfer.” Within that, transfer is further subdivided into “simple/near” (applying a mathematical formula to a new problem) and “complex/far” (applying a solution or principle from one knowledge base to another).

Strategies for effective learning

Spacing out learning across time

Next, a review of the two preferred techniques. First spacing, that “the timing of practice greatly influences learning success, even for the same overall quantity of practice.”

Citing Cepeda et al (2006), a meta-analysis that reviewed 254 studies with 14,000 participants and offering a table approaching 50 references categorised by learner age – the advantages of spacing, across domains and learner characteristics, is assured. Spacing benefits both memory retention and transfer.

Within the review there is one practice hidden gem:

“Spacing increases the risk of forgetting between learning sessions; spaced learning activities should provide sufficient practice with the material to permit any forgotten information to be relearned.”

Carpenter et al., (2022)

Retrieving information from memory

“When compared with study strategies that do not involve recalling information, retrieval practice typically generates more durable and accessible memories.”

More evidence, a second, even longer table.

A second hidden gem:

“Combining retrieval practice with learning activities that require the generation of new content such as thinking of examples, can yield even greater learning benefits than simple retrieval alone.”

Signposting back to Roelle and Nückles (2019) and Ebersbach et al., (2020). (Added to the reading list.)

Combining spacing and retrieval

“Spacing and retrieval practice can be combined to enhance learning more effectively than either strategy alone.”

Latimier et al (2021 would agree.

Here, Carpenter (2022) refer to the combined powers of retrieval and spacing as successive relearning.

Successive relearning involves an initial session in which learners try to retrieve the information they are learning and then receive feedback to check their accuracy, repeating retrieval practice until they are able to recall all of the information to a predetermined criterion. What most teachers might describe as a mastery approach. This initial session is followed by additional relearning sessions of retrieving the information followed by feedback until the information can be recalled again to the same criterion.

Successive relearning is most effective with a) extra retrieval practice in the initial learning session and b) when sessions are spaced apart, to which Carpenter et al., (2022) add, c) when retaining “fairly straightforward factual information.”

Referencing Rawson and Dunlosky, items that received extra initial learning retrieval practice were recalled 15% more 2 days later in the first relearning session (d=0.63), an advantage of that persisted over the subsequent two relearning sessions 8 and 10 days later.

Advice that most teachers should find hard to over look.

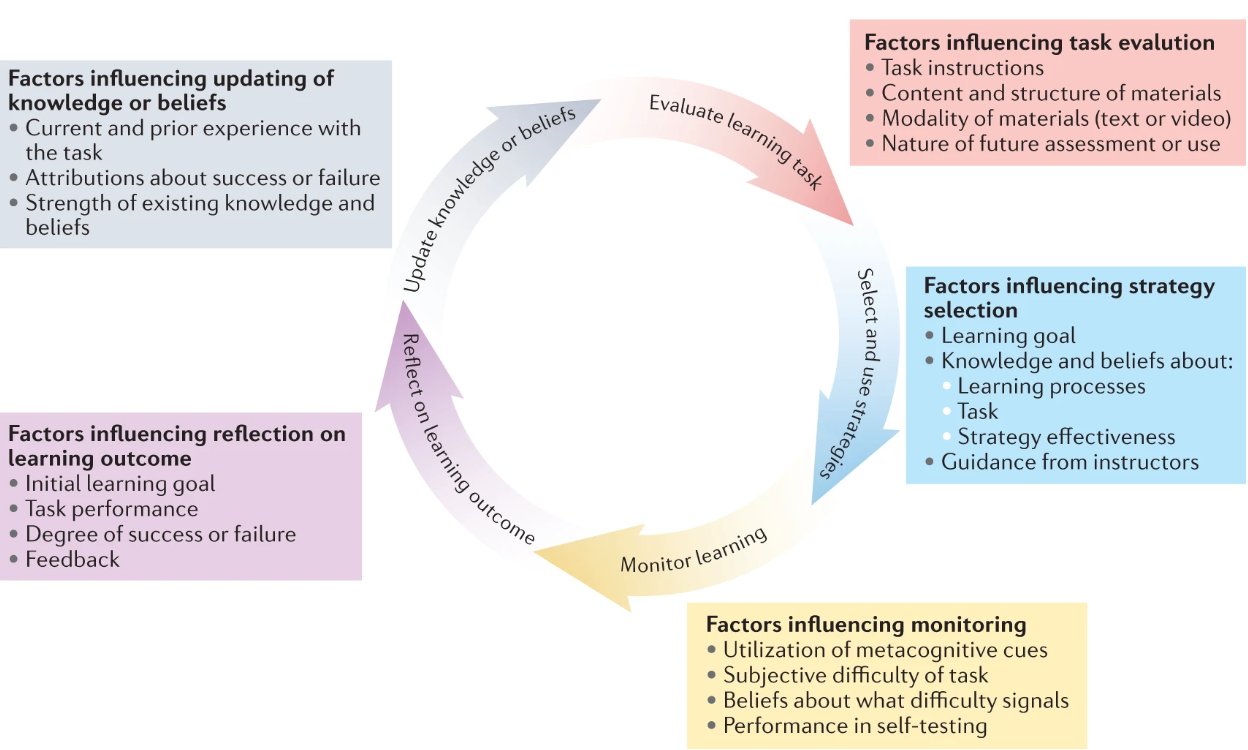

Metacognition of strategy use

Very swiftly, Carpenter et al., (2022) simplify and clarify their position. The paper focused on the use of effective learning strategies and self-regulated learning. The cognitive, motivational and affective processes that enable learners to plan, monitor and adapt their learning.

The nub of the issue is two fold. Learners “often demonstrate poor metacognitive control and make suboptimal decisions during learning.” Second, “most learners use these strategies to find out how well they know the information and not as a way of improving their learning, reflecting a lack of awareness of the direct benefits of retrieval practice.”

The paper moves on to recognise the importance of motivation – explored in a number of previous posts on this blog. Heitmann et al (2020) Pekrun (2018). A point picked up in an email conversation with Dr Carpenter following the paper being published.

I couldn’t agree more about the motivational value of quizzing and SR*. I have had very similar outcomes in my own classes, where students complete quizzes every day. They are not thrilled about this at first, but it doesn’t take long for them to directly experience the learning benefits, and then they actually enjoy it and use the quizzes to study even when they aren’t required to.

SR – Successive Relearning

On self-regulation, I have previously discussed the importance of metacognitive accuracy, in fact, I have referred to it as a “critical learning advantage.” In the previous post, Sotola and Crede (2020) reference the substantial gains made due to quizzing of our low prior attaining learners.

McDaniel and Einstein’s (2020) Knowledge – Belief – Commitment – Plan framework is an excellent starting point but those beliefs can be hard to shift. Yes to “time, practice, effort and support,” yes to the power of routines, yes to micro-reminders, all those mini wins, smart watch reminders, why not, but let’s not forget that experience can also be a great teacher. Include quizzing or #retrievalpractice right out of the blocks and explain what it contributes and recognise learning and employ relearning.

I was recently asked by a colleague with an interest in evidence informed practice – “how to” incorporate quizzing or #retrievalpractice with a new class, a science class in this case. Here is a short summary of my answer. Setting aside how to design a quiz… breadth, complexity, weight of knowledge. Reorder before refreshing questions.

- Quizzing with low failure rates (feedback is time expensive) and explain to pupils why you are quizzing (v basically)

- Quizzing as the routine. Collect and present results. (Compare to last year. Or another group. Or the same pupils pre quizzing)

- Stick with the quizzing plan. Routines take time to get established. 12-15 lessons is consistently reported as the time to build the routine by teachers using classroom.remembermore.app.

- Celebrate and recognise success. “Amazing! How do you know that?”

- Exploit the efficiencies of relearning. Keep failure rates low.

- Use self-assessment to develop metacognitive accuracy. Monitor accuracy. Collect and present results.

- Redesign the quiz to add desirable levels of difficulty – and keep the failure rates low.

Pingback: You can’t stop forgetting even if you try, but you can slow down – Edventures