This half term, I invested a good few hours with Engelmann and Carnine’s ‘Theory of Instruction.’ It was/is a challenging read, with plenty of opaque terminology, which even Engelmann himself recognises causes ‘arrhhhh’ moments here and there. I much needed diversion via two Engelmann video keynotes Engelmann (here and there) helped before I made my way back to the text, with a little more understanding under my belt.

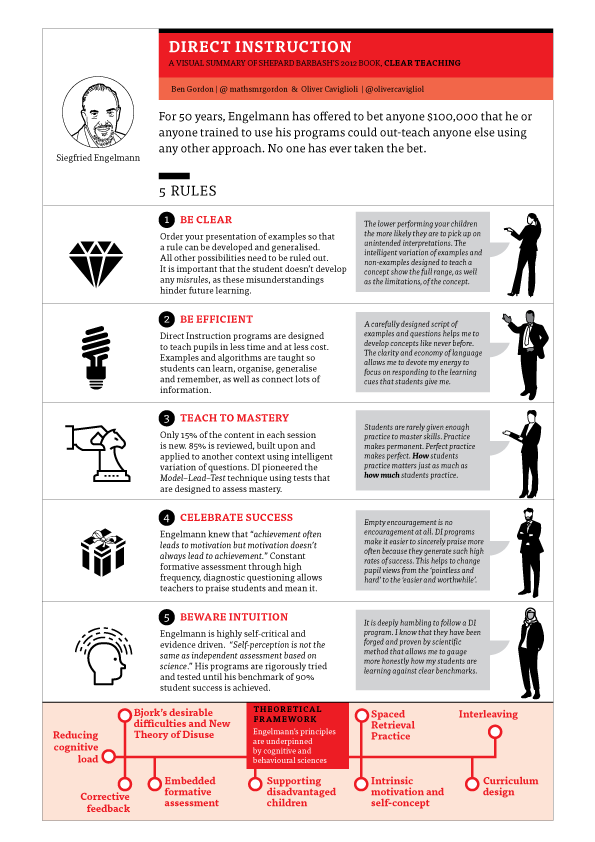

Of course, plenty of other educators have reviewed Englemann’s life’s work, with Ben Gordon’s @mathsmrgordon infographic (at the end of the this post) and ResearchEd’s Guide to Explicit and Direct Instruction just two signposts I followed. And no, it is not lost on me that I have now muddied the waters with addition of ‘Explicit.’ So what is Direct Instruction (capital ‘D’ and capital ‘I’ to distinguish it from a more generic model of ‘direct instruction’ often aligned with the work of Rosenshine).

Much of Engelmann’s work focused on special instructional methods and innovative curricular approaches using “planned variation” with elementary school children. Engelmann’s focus on the acquisition of basic knowledge and foundational language and numeracy skills (a bottom-up approach). Interestingly, as my thoughts on success-motivation-success evolves, Engelmann was already proposing the basic skills models would build self-esteem, arising from a mastery of component skills.

Two concepts about learning stood out for me. First, learners can learn any quality, defined as an irreducible feature exemplified through / from examples. (If the learner has not learnt, the teacher has not taught.)

Second, learners have the capacity to develop “rules” or “understandings” about common qualities or “sameness” to a set of examples. Once the learner has determined what is the same about the examples of the concept or quality, generalization occurs.

Armed with these two fundamental precepts, examples are structured to demonstrate a quality of “sameness.”

- Examples present only one identifiable sameness in quality – not more than one

- Communication signals the quality of sameness and the non-examples, those that do not share the quality of sameness.

- Examples demonstrate the range of variation that typifies the concept with each positive example only slightly different from each other.

- Non-example show the limits of variation in quality that is permissible for a given concept.

- Communication must provide a test to check whether the learner has received the information provided by the sequence of examples.

I therefore ‘presume’ that these structural conditions led to the adoption of the term ‘instruction,’ rather than teaching.

Empirically validated classroom testing yielded consistent beneficial outcomes for students, lifting the scores of disadvantaged students (at 20th percentile) in line with the national average (50th percentile). However, it also led to a rather ‘mechanical’ or systematic approach to learning the maligned response of the establishment was a topic which Engelmann wrote and commented upon widely. Simply, as often referenced by appraisers of DI, DI suffered from a ‘PR problem.’

Broad brush – Direct Instruction

- Presented stimuli to the learners (homogeneous groups)

- Carefully sequenced, scripted content aiming for ‘faultless communication.’

- Minimal new information (15%)

- Curated student responses to examples and non-examples presented at a high rate.

- Initially groups responses (10-14 a minute), periodically cold calling an individual students (checking for understanding) – highly interactive

- Positive reinforcement for correct responses.

- Errors are corrected immediately are evident.

- “Model, lead, test” more colloquially “I, we, you”.

- Learning through applied generalisations.

What it is not (non-examples)

- An absence of drawn-out teacher explanations.

Teach more in less time.

Becker (1992)

Reflections from the chalkface

I can not honestly profess to any fundamental change in my teaching or instruction as yet. I can however say that DI has impacted on my thinking. Of course, I recognise the fundamental difference of teaching Secondary schools pupils and foundational knowledge. Though some Secondary teaching is foundational.

I continue underline and notice “pupil attention,” and can often be heard saying, “without your attention, we are powerless.” I am thinking and preparing key ‘explanatory’ instructions.

If I student “hasn’t got it,” (but has attended) I am more prone to reissue the instruction and confirm understanding OR re-issue with a slight amendment and confirm understanding. It is my responsibility to ask the right question to the right student.

I found myself returning to using ‘group responses’ to a prepared question with an explicitly correct answer, that all students respond to. For efficiency and also to promote attention – (though I have quite often used copying responses where students “copy” a word, phrase, I present).

Finally, I have reconsidered my use of non-examples. Previously, I did not support teaching pupils what something was not. I see “non-examples” as explained by Englemann as framing the correct answer.

I very much doubt that DI with be far from my thinking, for both curriculum and instruction for some time.

Pingback: CLEAR TEACHING – Direct Instruction – Edventures