I recently shared a summary of Simonsmeier et al., (2022) work suggesting that pupil’s prior knowledge is a critical factor for teaching and accounts for about a third of the variance in learning outcomes.

On the back of summarising that paper, I went in search of some of the best research and every day illustrations. I figure you could borrow them for when you are leading staff professional learning?

Baseball in Milwaukee

In Norway, Wisconsin, as in much of the state, cold winters are a way of life. People allow extra time to bundle up and then waddle through their daily tasks. In 1987 two researchers from Marquette University in Milwaukee, Recht and Leslie (1988) ran an experiment as elegant in its simplicity as it was profound in its implications. Over several days, they invited 64 students to narrate half an inning of a made-up baseball game using a 18 by 20-inch replica baseball field, furnished with four-inch wooden figures. Students were asked to read the story and use the model to reenact the action. The passage began in the middle of the action:

Churniak swings and hits a slow bouncing ball toward the shortstop. Haley comes in, fields it, and throws to first, but too late. Churniak is on first with a single, Johnson stayed on third. The next batter is Whitcomb, the Cougars’ left-fielder.

All day long, Recht took copious notes, while Leslie, ran through the task with one student at a time. Each 12-year-old after another studied the passage and acted out the play:

The ball is returned to Claresen. He gets the sign and winds up, and throws a slider that Whitcomb hits between Manfred and Roberts for a hit.

Each student read carefully, laboured over every line, straining to capture each detail of the action.

Dulaney comes in and picks up the ball. Johnson has scored, and Churniak is heading for third. Here comes the throw and Churniak is out. Churniak argues but to no avail.

Every day, for two weeks, the four-inch figures were pushed and pulled across the field. Eventually, Recht gave each student a quiz designed to assess his or her baseball knowledge.

What did we learn?

Students with strong reading ability excelled? Students with good baseball knowledge excelled? Did baseball knowledge make no difference at all?

Pause for a moment to make your prediction before reading further.

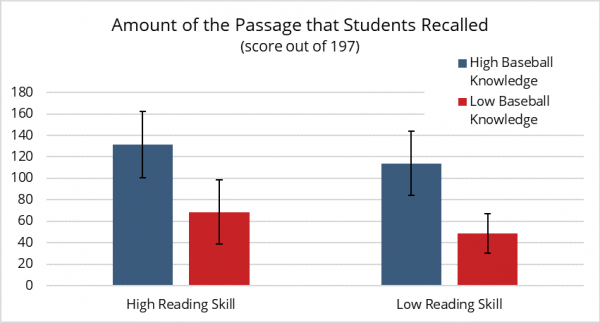

Recht and Leslie found that reading ability had little impact. Knowledge of baseball did. In fact, those who were weaker readers did as well as strong readers if they had knowledge of baseball.

Prior knowledge creates a scaffolding for information. For poor readers, the scaffolding allows them to compensate for their generally inefficient recognition of important ideas.

Recht and Leslie, (1988:19)

If students are taking a test, if the passage just happened to be about a topic they knew a lot about, they would outperform everyone else. But if they encountered a passage on a topic they knew little about, they would fare much worse.

Recht and Leslie showed that knowledge counts much more than we think in understanding text. It is hard to find the “main idea” of a piece of writing if you aren’t really understanding any of the ideas. Is a kangaroo rat large like a kangaroo or small like a rat? (Incidentally, it is neither a rat or a mouse, its closest relative being the pocket gopher). How does a rainforest feel when you are wearing a wool uniform like the English schoolboys did in Lord of the Flies? Prior knowledge can transform a poor reader into a capable one and a poor writer into a fascinating one.

Bransford and Johnson (1972) had me in a spin

Bransford and Johnson (1972) performed a classic set of experiments on schemas – aka prior knowledge. Read the paragraph below.

The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange items into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities that is the next step, otherwise, you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. In the short run this may not seem important, but complications can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. At first, the whole procedure will seem complicated. Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life. It is difficult to foresee any end to the necessity for this task in the immediate future, but then, one never can tell. After the procedure is completed one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, this is part of life.

Bransford & Johnson, (1972:722)

Now, on a scale of 1 (very hard) and 7 (very easy) rate:

- How easy was this passage was to comprehend?

- If working from memory, how easy would it be to recall and enact these instructions?

Now re-read the passage with the information that it is about ‘washing clothes’ and see whether it is easier to comprehend and recall and enact these instructions.

Bransford and Johnson (1972) had participants read this passage, rate its comprehension, and recall as much of the passage as they could under three conditions.

- No Topic control condition, participants were not told the topic of washing clothes.

- Topic Before condition, participants were told the topic before they read the passage.

- Topic After condition, participants were told that the passage was about washing clothes only after they read the passage.

Figure 1 shows the average results (in percentages) for comprehension ratings and recall. Mean percentage of comprehension rating and mean percentage recall of the Washing Clothes passage (Bransford & Johnson, 1972)

Knowing the topic ahead of time greatly increases ease of comprehension and recall of the passage. Even though both groups had similar knowledge about washing clothes, if the knowledge was not activated, then comprehension and recall suffered.

‘Topic After’ group are similar to those for the ‘No Topic’ group and much worse than for the ‘Topic Before’ group. In other words, activating the relevant schematic knowledge after reading the passage was no help at all in comprehending or recalling the passage.

What do we learn from this?

Teachers and textbooks often present a series of facts and then try to tie them all together with an overarching concept. This practice makes it hard for pupils to understand and learn material. The teachers, of course, know what the overall concept is, but the pupils don’t. It is the curse of knowledge.

Prior knowledge of a situation does not guarantee its usefulness for comprehension. In order for prior knowledge to aid comprehension, it must become an activated semantic context.

Bransford & Johnson, (1972:724)

So, teachers would be well advised to provide an overall framework first, then flesh it out with specific information. How prior knowledge is taught is critical to its future usefulness.

Full credit should be given to Dr Stephen Chew’s post “Having Knowledge Is Not the Same as Using It” here.

Chess games with Magnus

Watch world Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen put to the test by English Grandmaster David Howell. In the video he recognises famous games of chess and even recites the moves that followed. How can you not be impressed by the depth of his prior knowledge. Not forgetting Bransford and Johnson (1972) showed chess masters were able to recall and recognise the board configurations more accurately than the novice players, demonstrating the power of prior knowledge in shaping memory and cognitive processing.

In a similar vein, Dr Stephen Chew signposted this “Larnell Lewis Hears “Enter Sandman” For The First Time” video. Larnell Lewis is a Grammy Award winning musician, composer, producer, and educator. Larnell takes an analytical approach, breaks down all the details, noticing patterns and themes and how the different instruments play off each other. Because of this, he can already hum the chorus’ melody and drum part after only hearing the song once, and remembers most of the structure as well.

One more, Segall et al., (1963) the “Rice Paddy” experiment, showed participants a series of ambiguous figures that resembled objects found in a rice paddy. Participants from farming cultures were much more likely to identify the objects correctly than participants from non-farming cultures, demonstrating the power of prior knowledge in shaping perception.

Two final points. Let’s not forget, not all prior knowledge is positive – we often call these misconceptions. Learner beliefs about learning, often preconscious and often inaccurate, can be a more important driver of learning behaviour than a learners actual capability.

Reference