In spite (or because) of the complex relation between prior knowledge and learning, however, assessing learners’ prior knowledge before teaching them something new remains of utmost importance.

Dr Garvin Brod

The importance of prior knowledge can not be underplayed. Previously learned information organised in a learner’s memory has long been known to explain large portions of variance in learning outcomes across learning domains and learner characteristics.

Serving as the foundation upon which new knowledge is constructed, prior-knowledge includes a learner’s existing knowledge, experiences, and beliefs, and therefore is thought to influence not only how ‘sense data’ or information is processed and understood – but what is perceived in the first place.

A recent meta-analysis from Simonsmeier et al., (2022) of 439 studies, approaching 9,000 effect sizes found that prior domain knowledge is important for learning outcomes, particularly when the prior knowledge is directly related to the content being learned, but not necessarily for learning gains.

Let’s start by confirming what is defined as “prior knowledge”?

Simonsmeier et al., (2022) define prior knowledge as the “information, concepts, and procedures that individuals possess before engaging in a learning task”. Coded as declarative, procedural or declarative and procedural mixed. with subtypes: facts, conceptual knowledge, motor skill, and cognitive skill. The study focused on prior knowledge in specific domains: STEM, Language, Humanities, Social Sciences, Health Sciences, and Sports. The study also coded for learner, environmental and methodological study characteristics. The meta-analysis also examined the relationship between prior knowledge and different types of learning outcomes, such as memory, comprehension, and problem-solving.

What did we learn?

The meta-analysis found a positive relationship between prior knowledge and learning outcomes with an average effect size of 0.58. This means that prior knowledge accounts for about a third of the variance in learning outcomes.

The effect was found to be larger in some domains, such as mathematics and science, than in others, such as reading and language.

Prior knowledge had the strongest effect on memory tasks and the weakest effect on problem-solving tasks.

Specifically, Simonsmeier et al., (2022) offered five key findings:

- Prior knowledge is an excellent predictor of knowledge or achievement after learning

- Prior knowledge had close to average strong effect sizes in most studies

- Studies differed strongly in how prior knowledge affected learning

- The correlation between prior knowledge and posttest knowledge is different from the correlation between prior knowledge and knowledge gains. The former indicates stability in individual differences, while the latter indicates predictive power for learning something new.

- Absolute knowledge gains might sometimes underestimate the influence of prior knowledge on learning because they leave learners with high prior knowledge less room for improvement than learners with low prior knowledge

Thinking out loud

By distinguishing learning outcomes from learning gains, Simonsmeier et al., (2022) found that prior knowledge indeed explained large portions of variance in learning outcomes, but it did not, on average, explain variance in learning gains.

The former result indicates that those pupils in a class who know the most at the beginning of a class will likely know the most at the end as well. It also suggests that knowledge at the beginning of a class may not, in fact, determine how much a student will learn from a particular task or instruction. It may be argued that whether and how prior knowledge exerts an influence on learning will partly depend upon the prior knowledge itself. That looking only at the knowledge itself is not sufficient, as even large amounts of correct, specific, and coherent prior knowledge can be unused.

Takeaways

Simonsmeier et al., (2022) suggest that instructors should consider prior knowledge when designing instruction.

Future research should explore the best ways to activate and integrate prior knowledge to improve learning outcomes and “more precise and systematic theories of what kinds of prior knowledge facilitate learning, and under what conditions, are needed,” Simonsmeier et al., (2022: 20). Specifically studies of prior knowledge that induced differences in prior knowledge and the subsequent knowledge gains.

In response to the draft post, Dr Simonsmeier-Martin generously summarise the key findings from her paper for teachers.

So our research indicates that it is relevant to not only consider the amount of prior knowledge a student has (e.g., percentage of correctly solved math problems) but also the quality of their knowledge (e.g., misconceptions in science). Considering both facets of knowledge while teaching can help students in their learning.

Further, teachers can consider the cognitive demands of their teaching materials. For students with lower prior knowledge more guidance during the learning phase (i.e. lower cognitive demands) is likely to be more effective when compared to instruction/materials with higher cognitive demands. Students with higher prior knowledge don’t need as much support and are better off in learning environments with less guidance (expertise-reversal-effect).

Dr Simonsmeier-Martin

I note here, Dr Simonsmeier-Martin’s distinction of “the learning phase,” and potential impact of “high cognitive demands.” An information-knowledge distinction I continue to advocate in favour.

When prior knowledge helps or hinders learning

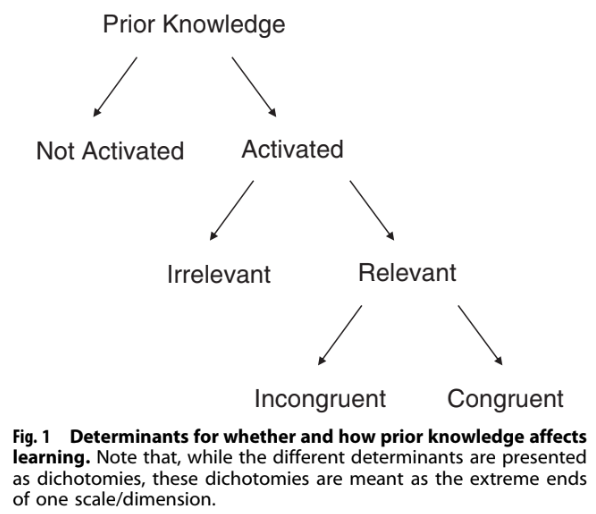

At this point, let me bring in a second paper, “Toward an understanding of when prior knowledge helps or hinders learning,” Brod (2021). Brod explores the complex relationship between prior knowledge and learning. Here, Brod (2021: 3) suggests “there are several determinants for whether and how prior knowledge affects learning,” Whether prior knowledge is:

- activated (i.e., information is retrieved from memory)

- relevant for the learning task at hand, and

- congruent or incongruent with the to-be-learned content*

Only when prior knowledge is activated, relevant, and congruent will it reliably help learning. Otherwise it quickly gets complex.

Dr Garvin Brod

Unravelling the systematics of whether and how this prior knowledge then steers the learning process is food for future research.

It is important to recognise that not all prior knowledge is facilitative. For example, if prior knowledge is relevant and accurate, it can help learners build a stronger foundation for new knowledge. However, if prior knowledge is inaccurate or irrelevant, it can actually impede learning by creating misconceptions or interfering with new learning.*

And finally, one important final point. Let’s not forget, as Dr Stephen Chew states, “useful prior knowledge is more than an accumulation of facts” and “having knowledge is not the same as using it.” And that “useful” is important (as Brod pointed out).

Dr Chew frequently outlines that prior knowledge is a complex network of connections and mental models that enable learners to process and integrate new information. Simply having prior knowledge is not enough; learners must be able to effectively use and apply this knowledge. This requires not only the acquisition [and maintenance] of new information, but also the development of metacognitive skills and strategies that enable learners to effectively manage and apply their prior knowledge, and in different contexts.

He recommendations therefore also include:

- providing an overall framework for learners first, then fleshing it out with specific information

- making sure that all the relevant information is activated for learners to comprehend and learn new concepts

- instructing learner to identify new situations in which schematic information is useful and should be activated

With reference to Bransford & Johnson, (1972) seminal paper, he concludes:

Prior knowledge of a situation does not guarantee its usefulness for comprehension. In order for prior knowledge to aid comprehension, it must become an activated semantic context.

Bransford & Johnson, (1972: 724).

The expertise reversal effect is when teaching methods that work well for beginners may not work as well for advanced learners because their needs and abilities have changed.*

Pingback: Illustrating why pupil’s prior knowledge is of the utmost importance – Edventures

Pingback: Critical teacher knowledge: working memory (part I) – Edventures