We don’t just need to change the sick note, we need to change the sick note culture so the default becomes what work you can do – not what you can’t.

The Rt Hon Rishi Sunak

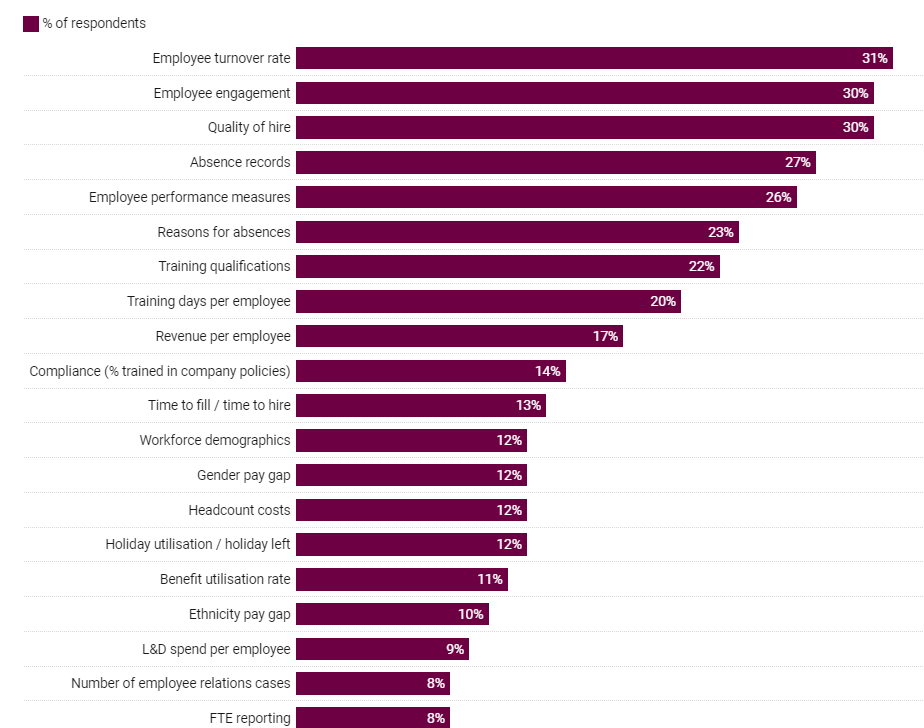

Is there a more significant people performance metric than employees being at work? It is, no doubt, a complex issue, without a simple or straightforward answer. In researching workplace attendance, I encountered a survey commissioned by HR software provider Ciphr, of 300 UK HR decision makers to find out which HR metrics they considered to be the most important to track. Although not in the top three, “absence/attendance” contributes twice, at places 4th and 6th.

Respondents were asked: In your opinion, which of the following, if any, are the most important HR metrics to track regularly within your organisation? They could select up to five options.

Sick note culture or made to feel guilty?

With workplace sickness and welfare reform thrust into the headlines care of the prime ministers speech on April 19th, there has been plenty to read and digest on the issue this past month.

I tend to agree with Dr Katie Bramall-Stainer, chairwoman of the BMA’s General Practitioners committee, rather than “pushing hostile rhetoric” the prime minister should focus on what is stopping employees/patients from receiving the healthcare and the support they need – so that they can work.

A flurry or articles and posts references a 2022 commissioned by MetLife. Here we are informed that three in five employees have not taken time off work for illness despite needing to. More than a quarter of employees (26%) say they would feel guilty if colleagues would have to pick up extra work if they called in sick (nearly twice as high for women (41%) then men (23%)). And in my humble experience, that concern is very much the case in school, moreover, teachers not only feel responsible for their colleagues workload but the impact of their absence on their pupils’ learning also. 17% felt concerned about the amount of work they would come back to and almost a fifth (18%) felt worried about how their line manager would react.

To add to the complexity of the issue, just 15% felt like they could take the time they needed to recover and only 13% felt that their employer cared about or was concerned for them.

And on the emergence of hybrid working options, I am not sure whether hybrid options help or hinder with this issue? In the one sense, hybrid working could offer a phased return to working without exposing others to germs/illness (there are many others reasons for genuine absence) and on the other, they could encourage an ‘always on’ workplace culture or expectation.

This point is picked up by, Adrian Matthews, Head of employee benefits at MetLife UK, signposts that the rise in presenteeism often leads to absenteeism in the long term.

This drive to work when illness strikes can prolong recovery, leading to employees suffering burnout later on, which can quickly lead to an unproductive workforce for employers.

Adrian Matthews – Head of employee benefits at MetLife UK,

I recognise I am only scratching the surface of the issue. Even so, it really does highlight the importance of contractual agreements, absence management procedures and employee benefits (for example income protection and pension contributions and access to a range of support mechanisms) and employees having access to advice and support, and of course access to their GPs in the first instance.

Workforce mobility on the increase, two in five UK employees willing pay cut for better benefits and employee absence (7.8 days per employee per year) at its highest rate in a decade – there is much to reflect upon and consider. It is, as Adrian Matthews comments “delicate balance.”

Big Question

How do ‘we,’ the employer, signal to staff (and prospective staff), that we are an organisation that will enable staff to pursue their individual purpose, both in and outside of work?