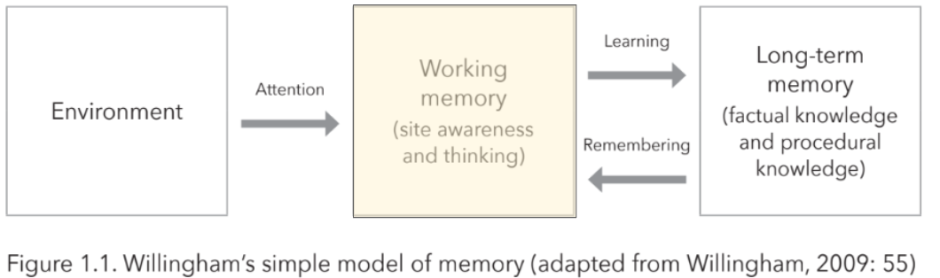

When it comes to cognition, to thinking, to memory, theory is unavoidable; therefore, a model is almost always inevitable. These memory models emphasise the importance of the environment, of attention, and help us to understand the mechanics or processes of learning (encoding-retrieval) and remembering (though rarely relearning) and long-term memory. Almost every account of the science of learning that I have read draws on Willingham’s simple model of memory or shares the key components of that model.

Focusing on working memory (I added the softlight), Alan Baddeley (2022) explains:

Working memory is a system for holding things in mind while you are working on them. It involves both a capacity to store information and also the capacity to manipulate it and relate it to other kinds of memory.

https://twitter.com/EvidenceInEdu/status/1512691346922000390

What Dr Tracy Alloway refers to as “our brain’s post-it note,” and Dr Susan Gathercole as “a mental jotting pad,” emphasising it’s small size, reminding us of its limited capacity, less so that it is “relatively fixed” capacity and its fragility. In fact, Dr Susan Gathercole often presents the case that working memory isn’t even a memory, “it’s the about an ability we have to hold in mind information.”

It is the ‘space’ where we attempt “to multiply 43 and 27 together” or order a list when we don’t have a pen and paper, where we remember the directions we asked for when we stopped because we lost our way.

More recently, I used the example of taking a list of four pupil names and putting them into alphabetical order. Four pieces of information should be accessible to most readers. Of course adding more names would increase the demands placed on working memory. This illustrates both the importance of the information and prior knowledge. The complexity of the information, syllable length, perceivable order, breadth of the alphabet covered, common first letters and prior knowledge of the alphabet clearly supports this task.

Try for yourself. Score the difficulty of each task out of ten.

- Dan, Cal, Bob and Amy (reverse order)

- Bob, Amy, Dan and Cal (no order, front of the alphabet)

- Bertrude, Annabella, Dominique and Constance (front of the alphabet, longer names)

- Stephanie, Cassandra, Paloma and Nathaniel (longer names, great breadth of the alphabet)

- Cassandra, Paloma, Pandora and Orlando (requires three letter order for Paloma ad Pandora)

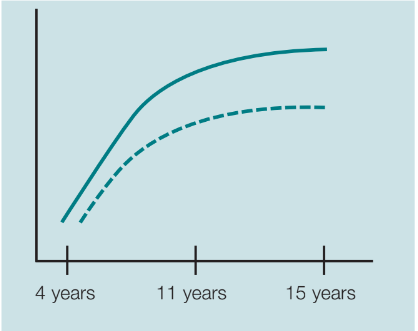

More recently, researching and writing Test-enhanced learning, I read that working memory capacity increases gradually until the teenage years (Swanson, 1999) and that capacities increase by about three times between the ages of 4 to 14 years of age, (declining again in our senior years, 56 years). With Gathercole and Alloway’s Classroom Guide sharing this graphical representation.

I also read that individuals who have poor working memory capacities in childhood do not catch up with those of their peers in adulthood.

I learnt that working memory capacity is effected by the characteristics of the information being processed (if there is an herent pattern / sequence / commonality for example) and the greater benefit of test-enhanced learning for pupils with lower working memory capacity (although the wider literature shows a mixed set of results).

I read plenty about the importance of prior knowledge theoretically off-setting the cognitive demands placed on working memory.

There has been plenty written recently about the power of classroom routines and the importance of directing attention to reduce “cognitive load.” There are generalised warnings about the potentially catastrophic effects of being distracted and the detrimental effects of retrieval interference. And yet, still, that softlighted box – “Working Memory (site awareness and thinking)” disguises a level of complexity that teachers would benefit from knowing more about.

I was first introduced to the subsystems of working memory during Oliver Caviglioli’s presentation on ‘Dual Coding’ at the 2019 ResearchED National Conference. However, I can remember that at the time, I struggled to keep pace with Oliver’s erudite explanation of the “visuospatial sketchpad,” and “auditory loop,” and how the information or sense data being received is treat differently, whilst admiring his graphics. Fast forward, four years and I happened to be reading a number of educational psychologist reports and the frequent references and inferences to issues of different aspects of working memory caught my attention.

In Part III I will aim to unpack the term working memory and show what teachers may benefit from knowing – what’s in the “working memory” box – that is not a box and may not even be memory.

Pingback: Critical teacher knowledge: working memory (part I) – Edventures

Pingback: What’s in the working memory box (part III) – Edventures

Pingback: Working memory – takeaways and reflections (part IV) – Edventures