Back in 2011 I read a Purdue Newsroom release and a series of press articles about Jeff Karpicke’s retrieval research.

Our research shows that practicing retrieval while you study is crucial to learning,” the study’s author Jeffrey D. Karpicke, an assistant professor of psychological sciences who studies learning and memory said in a press release. “Self-testing enriches and improves the learning process, and there needs to be more focus on using retrieval as a learning strategy.”

www.thestar.com – The best way to study is to take a test

I remember two points quite clearly. First, the 50% improvement results. Not the details, just the 50% better on the test one week later. Second – a comment about “… the struggle helps you learn,” and at that point in my teaching career, I was very much in favour of making learning tough, students working hard. I still am to a degree. The subtle change, I am more interested in what they are paying attention to, and what they are thinking hard about, rather than “work-harding” per se. But that insight comes from a further ten years of teaching.

Three years incubation

It took three years to turn insights into classroom practice. Teaching a boy heavy English class preparing for mock exams (some with high absenteeism or disengaged and most with low prior attainment and a good few hard working). I used free-recall retrieval to secure the key terminology for English GCSE Paper 1. It brought a degree of focus to lessons and success.

I continued to use a range of retrieval-type activities, in various formats, before that initial experience encouraged the adoption of retrieval practice strategies with a Year 8 all-boy low prior attaining English class in 2019, reigniting a professional interest in the retrieval research. However, it was soon evident that an understanding of ‘retrieval practice alone’ was not enough.

The term retrieval is misleading as it implies a terminal strategy. Testing is, and informs, learning, so pre-test, test during and post-test are all important.

Test-enhanced learning: A practical guide to improving academic outcomes for all students.

More than ten years after reading the first press release, three years edventuring, more than 350 research papers later (it may be more, I have them stored, 282 references in the book), conversations with researchers, teachers, pupils and parents, class based trials and iterations, led to an educational weave that I hesitantly refer to as “test-enhanced learning.” I say hesitantly as this field of cognitive science research is awash, and sufferers from, compounding terminology.

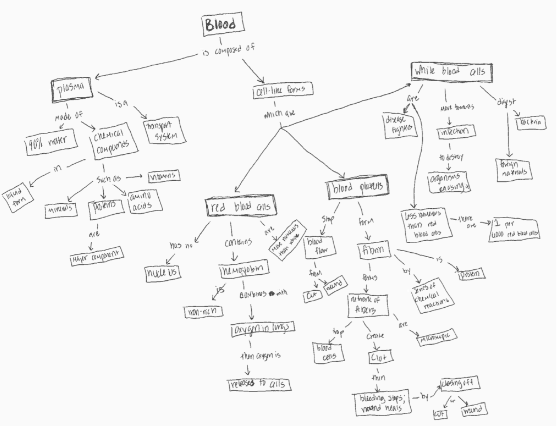

A weave that draws together:

Memory, learning, encoding and retrieval

Test-enhanced learning and (repeated) repeated retrieval practice

Spaced retrieval practice

Interleaving

The importance of feedback, the power of hints and the art of elaboration

Successive relearning

Metacognition and testing

Overcoming illusions of competence and personalisation

Testing, motivation and achievement

Under the umbrella term test-enhanced learning.

What now?

The final manuscript was returned yesterday.

What next?

Well, I hope we get to discuss the book and how you use test-enhanced learning in your context following its imminent release in December. There is no doubt in my mind that there is more required of teachers than to merely ask pupils to retrieve information from long-term memory – in whatever format or whatever stakes. There’s curriculum sequencing decisions, there is overcoming the pupils’ illusions of competence and lack of confidence in test-enhanced learning strategies. There are issues of motivation to explore further and to at least consider. There is of course – the not so easy task of building and managing the teaching routines to leverage the learning gains of test-enhanced learning. And possibly the greatest opportunities may lay beyond the classroom with either self-directed learning or personailsed spaced retrieval practice, offering “larger gains still.” I look forward to hearing from you.

If the eventual goal is to be able to retrieve that knowledge from memory, perhaps practicing retrieval of that information would be a better way to learn. Indeed, retrieval practice is one of the most effective ways of solidifying new knowledge, although this fact is underappreciated by most learners (and teachers).

McDermott (2020: 609)