So we are onto Week 2 of this FutureLearn course.

Week 2: Engagement for learning

Before we start this weeks tasks, I want to propose that students can be engaged in the task or activity, that does not ensure that they are learning (what is intended, or relevant).

2.1 Engagement for Learning

New learning so far;

An approach response is behaviour that brings an individual closer to a reward. An approach response does not necessarily mean direct interaction by the individual.

An avoidance response is a response that prevents an unpleasant experience, avoiding something from occurring.

2.3 Reward in the brain

The course reviews the place of reward in learning. Which connects to a conversation I am having with Jarlath O’Brien on the relative merits of reward or recognising attendance.

What I learnt is that how the brain responds to reward varies from one individual to the next, including age (Van Leijenhorst, 2010), gender (Hoeft et al., 2008), our tendency to be impulsive (Joseph et al., 2016), as well as hormonal and genetic differences (Caldu and Dreher, 2007).

In response to “Share a time when you had a student who was very difficult to get on task – what did you do to engage them?” I responded,

Teaching is a messy business. To propose that a single action or strategy promotes engagement would be folly. “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

After the culture of a school, a classroom, a topic even, has been set and develops – engagement strategies of encouragement, expectation, environment, role, modifying the task difficulty (both increased challenge and support or scaffold), time, milestones, partnership / collaboration and shared responsibility. Self-selection or choice / agency. Equally important – student readiness? Sometimes backing off, and coming back to the task at a later point.

And then I thought, what if it the teacher who has misfired?

Of course, there is also a case for teacher err here. Did the task offer desirable difficulty, is the task a good fit for that learner? Is it the task that needs changing rather then the student need engaging? (I add that retrospectively).

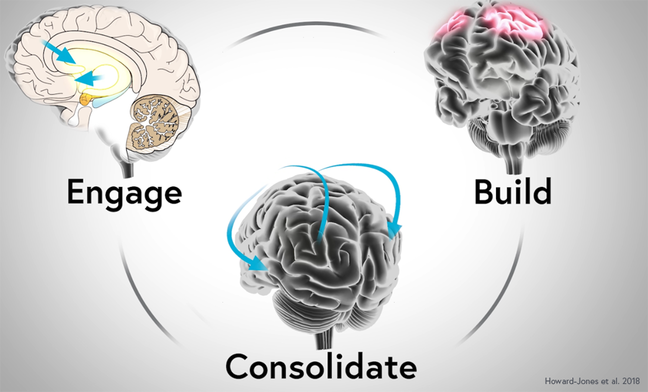

2.4 Neuromodulators help us learn

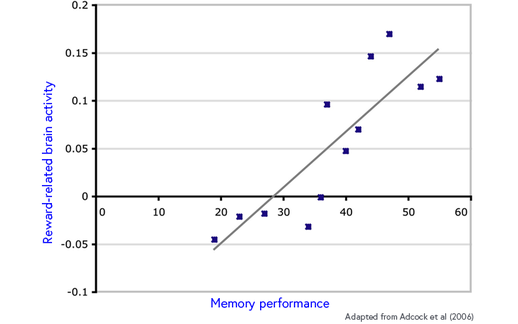

What I did learn is that that activity in the brains reward that

With anticipation of reward, there can be increased attention to the learning activity, and some studies have shown that this improves memory recall.

Moreover, novelty and uncertainty all stimulate learning. Topics that engage curiosity have been shown to stimulate activities in the brain’s reward regions (Min Jeong et al., 2009).

2.5 Students sharing knowledge and attention

Shared attention – when two or more people focus on the same thing can stimulate the brain’s reward system, encouraging us to engage and to learn. This links neatly with my recent exploration of oracy – as shared attention also helps explain how asking students to communicate their ideas in different ways, can engage their interest in their learning. This should not be surprising to us as teachers, surely having someone listen to you and your ideas is just another form of reward.?

2.6 Avoiding anxiety

The area of the brain involved with conscious attention is often referred to as the working memory network and is a region in the frontal cortex. Anxiety reduces the learners ability to sustain activity in the working memory network of the brain, less control over their working memory and a struggle to maintain their attentional focus. There is a far amount of interest and debate about anxiety of timed maths tests, used for committing number facts to long term memory.

2.11 Unconscious communication

Now this is fascinating stuff. We all know that emotions are “catching.” I can now say that it is due to the so-called Mirror Neuron System, not only does it help transmit attitudes and emotional responses – it may help learning through imitation.