In designing and building a teaching-instruction model, I was determined to enable the model to articulate. At least within the classroom, if not the wider Complex Adaptive System of the school in which it operates (of course schools then operate within the education system). That model is now posted as a series of five/six posts.

Previously, I had written a short explanation as to why classroom are both complex adaptive systems.

How are classrooms a complex systems

- they are dynamic, that is they are continuously changing

- they are far from equilibrium, classrooms have the potential to change suddenly and may take one of many paths

- the are open systems, that is, classroom interchange and interact with their surroundings

- they involve feedback (What happens next depends on what happened previously)

- they are systems where the whole is more than the sum of the parts

- are causal and yet indeterminate

In such systems, and many classrooms, (and schools),

- patterns emerge which cannot be predicted by looking at the parts of the system.

- a small number of patterns to which the system gravitates, has many starting points, the students (size of the class, composition, the physical space) for example.

- the surface complexity is the result of underlying simplicity.

- autopoeisis – that is the system may change it’s form or behaviour in order to maintain it’s identity.

- the system is composed of a “diversity of agents” that interact with each other, (our students, our relationships with our students) who mutually affect each other, and in so doing generate novel, emergent behaviour for the system as a whole. As is the case for class, each and every lesson.

- the system is constantly adapting to the conditions around it and over time it evolves.

- the spontaneous emergence of order.

- changes are irreversible, since the interaction of parts is transforming.

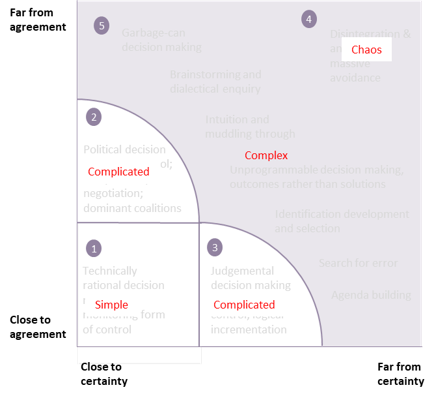

Teaching then, is about influencing the degree of certainty and agreement. Sometimes, I believe it is about reducing variability – purposefully and by design. When to flex and when to release. The later, a far more unpredictable and complex decision, one that required teachers to skilfully act on a range of classroom variables in order to change the relations and move the classroom productively out of a comfortable state of equilibrium, for greater gain. Knowing when to teach-assess-adapt and how evidence of that interplay informs the system.

Classrooms as Complex Adaptive Systems: A Relational Model

Any teaching-instruction model is accounting for literally hundreds of variables. The sheer number of variables at play, means that any model is generalising at best. Burns and Knox (2005) offer a typology of factors influencing classroom practices and I am sure you could add many more. Timetabling would include, time of the day, curriculum allocation, lesson length, single or double? Weather?

Institutional | Pedagogical | Personal | Physical |

| exam pressures time tabling and time pressures course aims and syllabus requirements required materials course focus on tertiary entry/study time available for preparation | previous lesson(s) student needs student skills/language ability newness of student experiences of tertiary study online classroom decision-making student age teacher-student relationships focus of the research project | language learning experiences previous training as (language) teacher previous teaching experience existing practices theories of teaching theories of learning recent study current study commitments personal lives and relationships | heat physical size and layout of class changes of rooms student movement in and out of class presence of researchers in classroom |

In a later paper, Burns and Knox (2011) compare classrooms with classic complex adaptive system description from de Bot, Lowie & Verspoor (2005a.)

Classrooms as complex adaptive systems

| de Bot, Lowie & Verspoor (2005a) | Burns & Knox (2005) |

| Complex systems are sets of interacting variables. | Classrooms are sets of interacting variables. |

| In many complex systems, the outcome of development over time cannot be predicted… because the variables that interact keep changing over time. | In many classrooms, the outcome of development over time cannot be predicted… because the variables that interact keep changing over time. |

| Dynamic systems are always part of another system, going from submolecular particles to the universe. | Classrooms are always part of another system, going from classroom, to institution, to an entire society. |

| As they develop over time, dynamic subsystems appear to settle in specific states, which are preferred but unpredictable, so-called ‘attractor states.’ | As they develop over time, classrooms appear to settle in specific patterns of practice, which are preferred but unpredictable, so-called ‘typical classes.‘ |

| Systems develop through iterations of simple procedures that are applied over and over again, with the output of the preceding iteration as the input of the next. | Classrooms develop through iterations of simple procedures that are applied over and over again, with the output of preceding iterations as the input of latter ones. |

| The development of a dynamic system appears to be highly dependent on its beginning state. Minor differences at the beginning can have dramatic consequences in the long run. … | The development of a classroom appears to be highly dependent on its beginning state. Minor differences at the beginning can have dramatic consequences in the long run. … |

| In dynamic systems, changes in one variable have an impact on all other variables that are part of the system: systems are fully interconnected. | In classrooms, changes in one variable have an impact on all other variables that are part of the class: classrooms are fully interconnected. |

| In natural systems, development is dependent on resources: … all natural systems will tend to entropy when no additional energy is added to the system. | In classrooms, development is dependent on resources: … all classrooms will tend to entropy when no additional energy is added to the class. |

| Systems develop through interaction with their environment and through internal self-reorganisation. | Classrooms develop through interaction with their environment and through internal self-reorganisation. |

| Because systems are constantly in flow, they will show variation, which makes them sensitive to specific input at a given point in time and some other input at another point in time. | Because classrooms are constantly in flow, they will show variation, which makes them sensitive to specific input at a given point in time and some other input at another point in time. |

In doing so, Burns and Knox (2011) found that viewing classrooms as complex adaptive systems helped further their understanding of classrooms as “relational.” Focusing on the features of complex adaptive systems, interaction, emergence, non-linearity, and nestedness, they provide a description of a classroom you may find familiar. At least I do.

Complex adaptive systems, classrooms, consist of multiple variables (highlighted in the typography above) that are constantly in interaction. As each variable ‘affects all the other variables contained in the system and thus also affects itself.’ The interaction of the variables of a classroom, present an inherent potential for instability and also, inevitably, change over time. Thus, it is unproductive to isolate individual variables as a way of describing a system. Rather, the trajectory of complex adaptive systems can be best mapped by the description of emergent patterns of behaviour. What are the observable emergent patterns of behaviour surfacing in our classrooms. How are these promoted or demoted? What variable add to the potential of instability?

Emergent behaviour is behaviour in a system which comes as a result of the interactions between different elements of the system (these cannot be explained by looking at the elements, but must take into account their relations and interaction in situ). Interactions between elements in a classroom emerge as ‘higher-order’ patterns of behaviour in a ‘larger’ system that operates on a different scale. Emergent behaviour cannot be predicted by looking at what parts of a system do in isolation, nor by identifying cause and effect relationships between variables.

Complex adaptive systems develop in a dialectic manner (multiple perspectives that led to the adoption of the most economical and reasonable solution). These perspectives are sensitive to initial conditions, and changes in systems are non-linear, aperiodic and irregular (it is one reason why lesson observations are so difficult). This is why the first few lessons can define a class climate for the academic year. While there may be periods of relative stability, there will also be times when the system becomes disturbed by the appearance of new, typically external, influences, (a new student for example or the absence of one) which can push the system in various unpredictable directions. It is why the presence of a bumble bee can destroy a class in an instant, only for the waters to be calm again next lesson.

Finally, complex adaptive systems are nested. That is, they are interconnected with other larger macro-systems systems or smaller subsystems. The various systems are themselves dynamic and are in continuous interaction with each other. For example, classrooms, department, school, education system.

What the teaching-instruction model was trying to account for was that classrooms are dynamic and complex, that there is an inherent potential for instability and unpredictability in classrooms, even highly structured, teacher-centred classrooms. Classroom action can unfold in a relatively predictable manner however, as with any complex adaptive system, unforeseen (and unidentified) factors can have an unpredictable impact (the bumble bee to a students absence), and when classrooms and the students that inhabit them are in a state of flux, linear cause-and-effect descriptions cannot comprehensively account for what emerges. Classrooms swamps.

Burns, Anne & Knox, John. (2011). Classrooms as Complex Adaptive Systems: A Relational Model. 15.

Burns, A., & Knox, J. (2005). Realisation(s): systemic functional linguistics and the language classroom. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied linguistics and language teacher education (pp. 235-260). (Educational linguistics). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

A Relational Model

Again, there is communication with illustration.

Burns, Anne & Knox, John. (2011). Classrooms as Complex Adaptive Systems: A Relational Model. 15.

Burns, A., & Knox, J. (2005). Realisation(s): systemic functional linguistics and the language classroom. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied linguistics and language teacher education (pp. 235-260). (Educational linguistics). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Pingback: Plans, cycles and spirals (part 1) | KristianStill

Pingback: Plans, cycles and spirals (part 2) | KristianStill

Pingback: Plans, meso-cycles and spirals (part 3) | KristianStill

Pingback: Plans, macro-cycles and spirals (part 5) | KristianStill

Pingback: Planning a scheme of work – workflow | KristianStill

Pingback: What you learn is more than what you see: what can sequencing effects tell us about inductive category learning? – Kristian Still

Pingback: What’s in the working memory box (part III) – Edventures