Tonight’s reading, “Techniques for scaffolding retrieval practice: The costs and benefits of adaptive versus diminishing cues.”

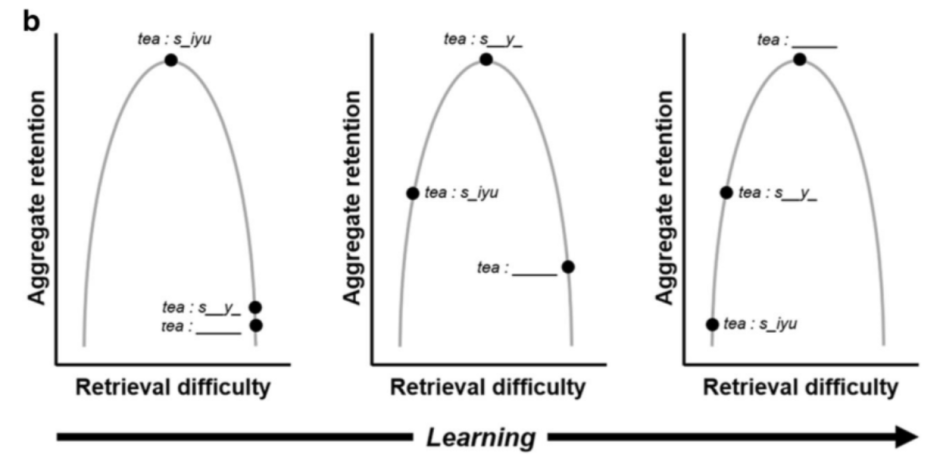

Fiechter & Benjamin (2019) are investigating retrieval difficulty. With difficulty manipulated by providing easier or harder, more or fewer retrieval cues. In this case letters of the target word. (English–Iñupiaq word pairs – e.g. tea–saiyu). I had to look up Iñupiaq – indigenous people of north-western Alaska.)

If the plan is to test multiple times, we could provide progressively fewer and fewer cues with each retrieval attempt. What is referred to as diminishing-cues retrieval practice (DCRP). That is, we could scaffold retrieval demands, until the learner could provide target information without assistance.

Diminishing-cues retrieval practice (DCRP) is used to maintain “effort” or difficulty. In a previous paper, Fiechter & Benjamin (2018) found that DCRP more beneficial than standard testing in the absence of feedback, and it was just as effective as testing when feedback was provided. In some sense, I would suggest the cues are feedback, in that they exclude a large proportion of possible answers.

However, what Fiechter & Benjamin were left to contend with, was subjective item difficulty. This subjective item difficulty lending itself to a more flexible approach to scaffolding called adaptive-cues retrieval practice (ACRP).

ACRP generates an optimally difficult retrieval attempt by first having a learner attempt a retrieval in the absence of any cuing and then provide increasingly informative cues until the learner would be able to retrieve the correct response. That is, it provides just enough assistance to learners in order for them to retrieve the correct response.

Fiechter & Benjamin (2018)

So here goes:

12 English–Iñupiaq word pairs (e.g. tea–saiyu). Every target word was five letters long.

Study phase: 4 seconds presentation, three times exposures. After the study phase, participants performed a distractor task for 1 minute.

Practice phase: Four practice conditions. Six rounds; overt retrieval.

In ACRP experiments 1a and 2b participants were shown the English target and five blank spaces; they were asked to either provide the Iñupiaq target or else press the space bar to request a letter. Letter presentation was randomly ordered. Letter requests could be made only after 2 seconds had elapsed since the last request.

In Experiments 3a and 3b, learners had to provide a response before they would receive each an additional letter. This routine continued until the correct response was provided or until all five letters of the target were shown.

In the DCRP condition, learners were initially shown a complete cue–target pair. Letters were randomly omitted, one at a time, from the target with each subsequent practice round until no letters remained by the final round of practice.

Final test: 12 to 36 hours after completing the first part of the experiment. All test trials were self-paced.

What do we learn?

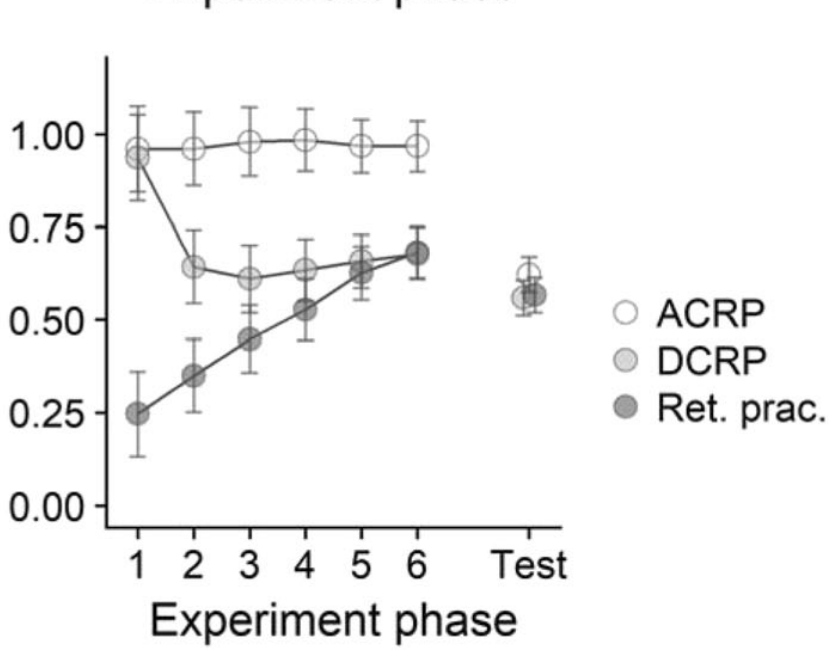

ACRP performed better than the two conditions when feedback was not provided, and similar performance between ACRP and retrieval practice when feedback was provided. DCRP was superior to standard retrieval practice without feedback and equally effective when feedback was provided.

2a and 2b directly compared the benefits of ACRP and DCRP to one another, with and without feedback. Fiechter & Benjamin (2019) found no convincing performance differences between ACRP and DCRP, and much shorter practice times for items in the DCRP condition.

Finally 3a and 3b evaluated the benefits of a “revised” ACRP technique against DCRP, without feedback (3a), and against DCRP and standard retrieval practice, with feedback (3b).

The revised version of ACRP, in which learners had to provide a response prior to receiving additional cuing, was superior to DCRP when learners were without feedback. However, it was even more time-consuming.

Conclusions

In this procedure, 1) adaptive learning schedules are effective and (2) scaffolded but nonadaptive retrieval is faster and just as beneficial as self-testing with feedback.

Of course, this procedure promotes empirical investigation. But can it be applied? The most obvious point, responses or target, are not going to be five letters in length. How do we apply a DCRP / ACRP model in reality? Of two “difficulty” adaptive methodologies, cuing and hints, I think I prefer the use of hints.

As for RememberMore, could we apply adaptive cuing/tagging? Turning off tags follow criterion success? Potentially.