A week ago I had the privilege of meeting with Bridgid Finn (Senior Research Scientist, ETS – the world’s largest private educational testing and measurement organization). After a series of email exchanges exploring interactions between motivation and cognition we meet to discuss my key question.

Accepting that this is an individual difference, what is desirably difficult?

Now I wished that I had recorded that conversation however Bridgid was eloquent, knowledgeable and boy did she put forward a strong case for motivation, sufficient for Bjork and Bjork (2020) to state that “issue of motivation” must be addressed and that their eyes had been opened with respect to the challenges that remain.

Following the meeting, Bridgid shared two papers she thought “may be of interest.”

Dietrich et al, (2019) “In-the-Moment Profiles of Expectancies, Task Values, and Costs” and Tanaka and Murayama (2014) “Within-person analyses of situational interest and boredom: Interactions between task-specific perceptions and achievement goals.”

Which to pick first?

I will be honest with you – I am not overly familiar with motivation research beyond Pekrun’s papers. Even the paper titles were intimidating. I did recognise Kou Murayama from Pekrun’s work and Bridgid had explained the role that “Task Value” and “Costs” play in motivation for learning during our meeting. If you then add “expectancy of success” and you have raw components of Expectancy-Value Theory. So – I went with Dietrich et al, (2019).

It quite literally took me a week to understand the paper, and even then, I am not 100% assured of my own understanding. Why did it take so long? Well, in order to get under the skin of the paper, you had to first understand Expectancy-Value Theory. So, the plan is to share that edventure, that diversion, before coming back to Dietrich et al, (2019).

What is motivation?

Research on achievement motivation has a long and distinguished history, referred to by the American Psychological Association as:

the desire to overcome obstacles and master difficult challenges.

American Psychological Association

Motivational theories fall into four broad categories, those that focus on:

- beliefs about competence and expectancy for success;

- reasons why individuals engage in different activities;

- integrating expectancy and value constructs;

- drawing links between motivational and cognitive processes.

This post focuses on the third category, expectancy and value constructs.

The role of achievement motivation in learning has demonstrated that there is a strong relationship between prior performance, achievement motivation and future achievement outcomes. Bear this in mind as I attempt to unpick the importance of Expectancy-Value Theory (EVT) of achievement motivation to your teaching, your classrooms (and to your own personal professional learning).

Expectancy-Value Theory

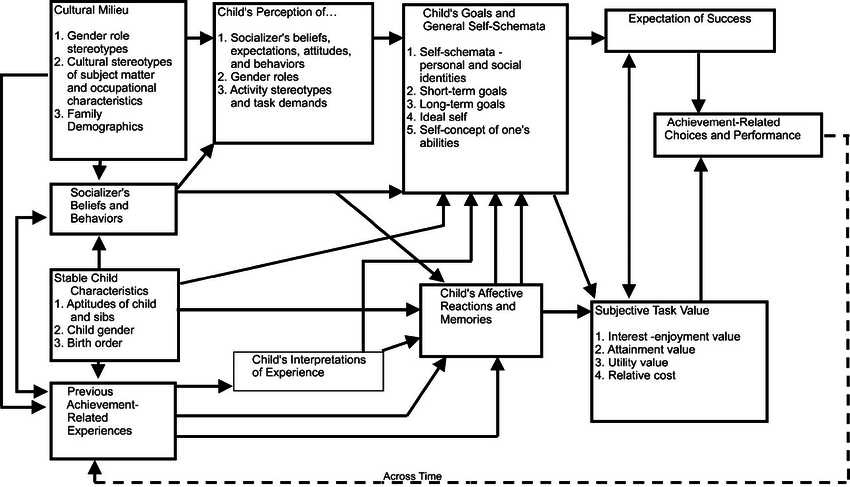

Expectancy-value theory (EVT) of achievement motivation (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000) offers a widely applied theoretical framework that can be used to explain the relationship between motivation and achievement performance. Their complex and sophisticated model took some time to get to grips. I also read a more recent summary Eccles & Wigfield, (2020).

Expectancy-value theory highlights the dual importance of competence-related beliefs (expectations for success) and values in explaining motivation.

The theory postulates that achievement-related choices are motivated by a combination of a learner’s expectations for success (“Can I learn this?”) and subjective task value (“Why should I learn this?”) in particular domains.

Expectancy-value theory further differentiates task value into four components: Interest, intrinsic value (personal enjoyment), attainment value (importance of doing well), utility value (perceived usefulness for future goals), and relative cost (competition with other goals).

Cost is identified as a crucial component in value and refers to opportunity and emotional cost for engaging in tasks and the amount of effort required to succeed.

According to the expectancy-value model, expectations of success and task value are shaped by a combination of factors. These include abilities (previous experiences, goals, self-concepts, beliefs, expectations, interpretations) and environmental influences (cultural milieu, socialisers’ beliefs and behaviours).

Research has demonstrated that expectations for success and task value are distinct constructs. Second, that expectancies for success tend to predict learners’ later task value. That is, learners tend to value the domains in which they feel competent.

And that makes sense? We value those tasks where we have situational confidence and have experienced success in the past, or are experiencing success?

Both factors predict learners’ achievement-related outcomes however expectations for success are more strongly linked to performance. For example, a learner who believes she will do well, tends to get higher grades than a learner who does not expect to do well. Task values are more strongly tied to achievement-related choices. For example, a learner who values mathematics is more likely to take advanced mathematics than a learner who does not value mathematics.

How am I doing so far? Ready for the next step?

Task-related value beliefs (“Why should I learn this?”) and expectancies learners hold about their success in a task (“Can I learn this?”) are central antecedents of learner engagement and their behaviour in class (Eccles and Wigfield, 2002). Remember, achievement behaviour is largely influenced by expectancies of success and subjective task values.

Task values, (attainment value, intrinsic value, utility value and cost) are of particular interest in a discussion of retrieval practice, successive relearning and desirable difficulties because it relates students’ affective reactions to previous experiences (experienced effort and difficulty) to achievement choices. It is the conundrum I have been wrestling for quite some time.

Accepting that this is an individual difference, what is desirably difficult?

If you are still with me – then thanks for sticking with the post. In part 2 I’ll answer the question:

Why should teachers be interested in expectancy and value ratings?

Eccles, J. S., and Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 109–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

Dietrich, J., Viljaranta, J., Moeller, J., and Kracke, B. (2017). Situational expectancies and task values: associations with students’ effort. Lear. Instr. 47, 53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.10.009

Dietrich, J., Moeller, J., Guo, J., Viljaranta, J., & Kracke, B. (2019). In-the-Moment Profiles of Expectancies, Task Values, and Costs. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1662. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01662

Tanaka, A., & Murayama, K. (2014). Within-person analyses of situational interest and boredom: Interactions between task-specific perceptions and achievement goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(4), 1122–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036659

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, Article 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Pingback: Adapting quizzing: perception of cognitive load #retrievalpractice – Edventures

Pingback: Test-enhanced learning: On my terms (Part I) – Edventures